Financial Assurance

The assurance system for financial accounting is an obvious referent for AI assurance. Some existing financial sector laws may be directly applicable to AI.326 Otherwise, they may still furnish useful analogies. In other words, as one commenter stated, “the established financial reporting ecosystem provides a valuable skeleton and helpful scaffolding for the key components needed to establish an AI accountability framework.”327

In the financial sector, a standard setting body develops guidelines for how an auditor should assess the financial disclosures of a business. Then, an independent certified professional evaluates that business against those standards.328 The goal of a financial audit is to give investors assurance that they have high quality information about the business, which in turn aids the public trust in the capital markets. Audits cover both governance controls and metrics for reporting financial information, and they are structured as reviews of management’s certified claims about each.329

The modern legal and regulatory regime governing the financial services sector—including for reporting and disclosure obligations—is partly a response to major, global financial crises that disrupted the economic order and led to calls for increased oversight.330 At the federal level, financial sector risks have focused the attention of lawmakers seeking to protect investors and promote a trustworthy marketplace.331 Congress has passed a variety of laws since the 1930’s, including the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and Sarbanes-Oxley, which aim to foster accountability in the financial sector.332 A detailed analysis of these legal regimes is out of scope of this Report, but the general structure around financial accounting/reporting and related auditing standards—particularly for public companies subject to securities laws—is an area worth exploring to further AI accountability.333

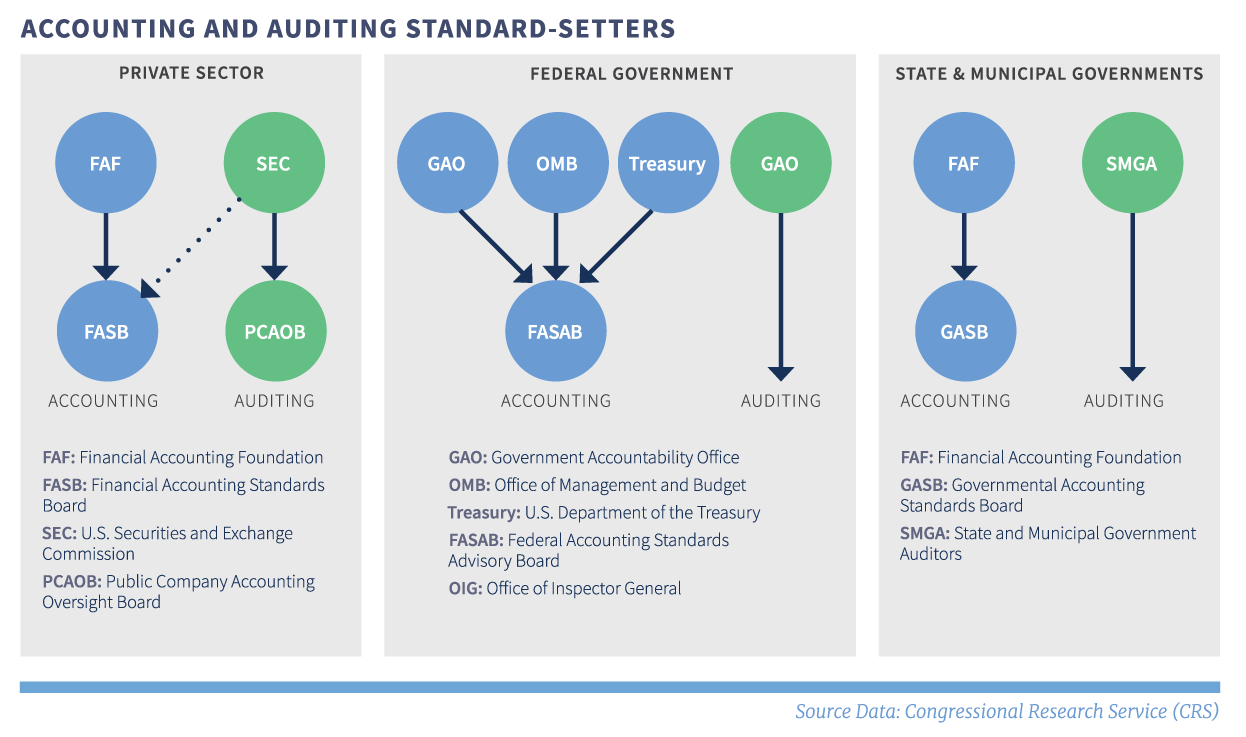

Financial accounting and auditing standards for public companies are established through a public-private collaborative process, subject to key federal government oversight and federal participation in the process. For accounting standards, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has the authority to recognize “generally accepted” accounting principles developed by a standards-setting body. By law, this recognition must be based on the SEC’s determination that the standards-setting body meets certain criteria, including “the need to keep standards current in order to reflect changes in the business environment[]” and can help the SEC fulfill the agency’s mission because, “at a minimum, the standard setting body is capable of improving the accuracy and effectiveness of financial reporting and the protection of investors under the securities laws.”334 Today, the SEC recognizes the independent non-profit Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) as the designated private-sector standards setter, and considers its set standards as “generally accepted” under Sarbanes-Oxley.335 The SEC has made clear that there is federal oversight of this structure and the SEC continues to have an important role in the standards’ recognition.336

For auditing standards, Sarbanes-Oxley created the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB), a non-profit corporation that is subject to SEC oversight.337 Oversight includes the SEC’s “approval of the Board’s rules, standards, and budget.”338 PCAOB itself is tasked with “oversee[ing] the audit of companies subject to securities laws.”339 Among its duties, PCAOB must, based on certain SEC actions, “register public accounting firms that prepare audit reports,” “establish or adopt . . . auditing. . . and other standards relating to the preparation of audit reports,” “conduct inspections of registered public accounting firms,” “conduct investigations and disciplinary proceedings concerning, and impose appropriate sanctions where justified upon, registered public accounting firms and associated persons of such firms.”340 The SEC may determine additional duties or functions for the Board to enhance the relevant audit landscape.341 In furtherance of its mission, PCAOB has established a series of auditing and other standards related to financial auditing.342

Congressional Research Service, supra note 333, at 2. The graphic is accompanied by the following note: “In the first panel, the striated line indicates the SEC’s oversight role over accounting standards promulgated by the FASB. The FASB’s parent organization, the Financial Accounting Foundation (FAF), is a nonstock Delaware corporation. Neither FASB nor FAF is a government agency, even though the SEC does have oversight of the budget for FASB and the accounting standards as promulgated by FASB (FAF, “Facts About FAF,” http://www.accountingfoundation.org/jsp/Foundation/ Page/FAFSectionPage&cid=1176157790151).” Id.

Thus, accounting and auditing standards for the financial sector, subject to public securities law, are structured to permit non-governmental entities to lead in the creation of standards but give regulators the chance to contribute to and oversee the standards-setting process.344 While such structure is not without criticism,345 it has proven to be relatively effective in providing assurance about audited financials.

A review of the comments yields composite recommendations to use certain features of the financial accountability model for possible adoption in the AI accountability space. Some ideas include:

- Forming audit oversight boards, similar to the PCAOB, to train auditors, assess their qualifications, and adjudicate conflicts of interest.

- Imposing annual requirements for public companies that are AI actors to assess the effectiveness of their internal controls over AI risk management, documentation, and disclosure and have auditors attest to the company’s assessment. This is analogous to what is required of public companies with respect to financial reporting.

- Clarifying that because AI audits can take many forms and answer different questions, disclosing the terms of engagement and audit methodology creates critical context.

- Encouraging collaboration between AI actors and regulators on risk management. In the words of one commenter, collaboration between financial institutions and their regulators “illustrates that a tailored yet flexible approach provides strong accountability measures that also allow industry to innovate.”346

- Establishing a federal regulator with cross-sectoral authority to oversee the implementation of AI standards.

326 See, e.g., Intel Comment at 3 (“[T]here are numerous existing laws or regulations that apply to the deployment and use of AI technology, such as state privacy laws, federal consumer financial laws and adverse action requirements enforced by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, constitutional provisions and Federal statutes prohibiting discrimination under the jurisdiction of the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division, and the Federal Trade Commission Act which protects consumers from deceptive or unfair business practices and unfair methods of competition across most sectors of the U.S. economy.”); Morningstar, Inc. Comment at 1 (“Morningstar believes that new AI-specific regulation may not be necessary because current financial regulations are generally drafted broadly enough to encompass AI products and their use.”).

327 PWC Comment at 1. See also id. at A4 (“In developing an AI accountability framework, we recommend that policy makers look to the financial reporting ecosystem as the gold standard in ensuring the reliability of, and market confidence in, company-specific information.”).

328 See, e.g., Paul Munter, The Importance of High Quality Independent Audits and Effective Audit Committee Oversight to High Quality Financial Reporting to Investors, United States Securities and Exchange Commission (October 26, 2021).

329 PWC Comment at A4.

330 See, e.g., PWC Comment at 1 (“Notably, however, the ecosystem around financial reporting is a child of crisis: the stock market crash of 1929 created the initial requirements for reporting by and audits of public companies while the high-profile collapse of companies such as Enron in the early 2000s led to enhanced responsibilities for management to provide reporting around internal control over financial reporting.”); U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Financial Services, Report on the Corporate and Auditing Accountability, Responsibility, and Transparency Act of 2002, H. Rept. 107-414 (April 22, 2002), at 18 (“Following the bankruptcies of Enron Corporation and Global Crossing LLC, and restatements of earnings by several prominent market participants, regulators, investors and others expressed concern about the adequacy of the current disclosure regime for public companies. Additionally, they expressed concerns about the role of auditors in approving corporate financial statements. . . .); William H. Donaldson, Testimony Concerning Implementation of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (September 9, 2003) (“Sparked by dramatic corporate and accounting scandals, the [Sarbanes-Oxley] Act represents the most important securities legislation since the original Federal securities laws of the 1930s.”).

331 U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, About the SEC (“The mission of the SEC is to protect investors; maintain fair, orderly, and efficient markets; and facilitate capital formation. The SEC strives to promote a market environment that is worthy of the public's trust.”). See also U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, Mission.

332 U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, The Laws That Govern the Securities Industry (listing various securities laws).

333 The legal and regulatory structure of the financial services sector is complex, and for the purposes of this Report, we principally focus on financial accounting and auditing standards in the private sector. The federal government and state and local governments have their own accounting and auditing mechanisms. See, e.g., Congressional Research Service, Accounting and Auditing Regulatory Structure: U.S. and International (Report R44894) (July 19, 2017), at 11-18 (providing descriptions). These structures may also be worth analyzing further in the context of developing AI accountability measures.

334 Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, 116 Stat. 745, Section 108(b)(1)(B) (2002).

335 U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, Commission Statement of Policy Reaffirming the Status of the FASB as a Designated Private-Sector Standard Setter, 68 Fed. Reg. 23333 (May 1, 2003). On its own authority, the SEC since 1973 has recognized FASB’s financial and accounting reporting standards as authoritative, but Sarbanes-Oxley helped provide a clearer, updated structure from Congress that the SEC could rely on to determine whether the standard-setting body produced “authoritative” or “generally accepted” financial accounting and reporting standards.

336 U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, 68 Fed. Reg. at 23334 (“While the Commission consistently has looked to the private sector in the past to set accounting standards, the securities laws, including the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, clearly provide the Commission with authority to set accounting standards for public companies and other entities that file financial statements with the Commission.”) (citing Section 108(c) of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, which states, “Nothing in this Act, including this section...shall be construed to impair or limit the authority of the Commission to establish accounting principles or standards for purposes of enforcement of the securities laws.”). See also Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, Section 108(b)(1)(B) (“In carrying out its authority under sub-section (a) and under section 13(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, the Commission may recognize, as ‘generally accepted’ for purposes of the securities laws, any accounting principles established by a standard setting body.”) (emphasis added); Financial Accounting Standards Board, SEC Accepts 2023 GAAP Financial Reporting Taxonomy and SEC Reporting Taxonomy (March 21, 2023) (“The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) today announced that the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has accepted the 2023 GAAP Financial Reporting Taxonomy (GRT) and the 2023 SEC Reporting Taxonomy (SRT) (collectively referred to as the ‘GAAP Taxonomy’). The FASB also finalized the 2023 DQC Rules Taxonomy (DQCRT), which together with the GAAP Taxonomy are collectively referred to as the ‘FASB Taxonomies.’”).

337 See generally Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, 116 Stat. 745 (2002), title I; Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, About.

338 Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, About.

339 15 U.S.C. § 7211(a).

340 15 U.S.C. § 7211(c)(1)-(4).

341 See 15 U.S.C. § 7211(c)(5).

342 Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, Standards; Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, Auditing Standards of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (latest auditing standards, for fiscal years ending on or after Dec. 15, 2020).

344 Id.

345 Sarah J. Williams, “The Alchemy of Effective Auditor Regulation,” 25 Lewis & Clark Law Rev. 1089, 1107 n.105 (2022) (collecting sources criticizing auditing standards and PCAOB)..

346 SIFMA Comment at 2-3.